For some of the witnesses called to appear at the Catalan independence trial, answering questions put by the private prosecution conducted by the extreme-right political party Vox has required some soul searching. Former Catalan parliamentarians for the CUP party, Eulàlia Reguant and Antonio Baños, refused on moral grounds to answer the Vox lawyers’ questions and this made it impossible for them to give any testimony at all, after being called to court by the defence teams. Other witnesses have chosen to register their protest but nevertheless make their declarations. This was the case last week of another former CUP deputy, David Fernández, and on Monday, of legendary singer-songwriter Lluís Llach.

Llach, also a former deputy but best known for his Catalan protest songs, had been called to appear by Vox as a result of his presence at the key protest outside the Catalan economy ministry on September 20th, 2017. He began answering the questions of the Vox lawyer, party secretary Javier Ortega Smith, but after a minute and a half and four responses he felt he had to say something important. He asked the presiding judge, Manuel Marchena, for permission to tell the court that "as a homosexual and pro-independence citizen, and aspiring citizen of the world" he disagreed with having to respond to the questions from Vox.

Marchena's response to such moments is strictly by the book. "The court respects your lifestyle completely, in absolutely everything. It only wants the proceedings to be carried out as established by law," he said.

Questioning the private prosecution

But on Monday, the day after the Spanish election which had converted the Vox lawyer and party number two Ortega Smith into a deputy-elect of the Spanish Congress, the presiding judge went a little further.

He explained to the witness that the lawyer questioning him "represents the private prosecution" and that this is an element allowed under the Spanish legal system. But he admitted the possibility of questioning not only the presence of Vox but the very existence of a private prosecution. "Anyone can have an intellectual attitude about the existence or otherwise of the private prosecution but it is included in the judicial system," he argued.

Judge Marchena spoke as if Llach had raised not an ethical debate about the difficulty that he had in responding to Vox, but a legal debate about the very existence of this juridical provision.

No violence

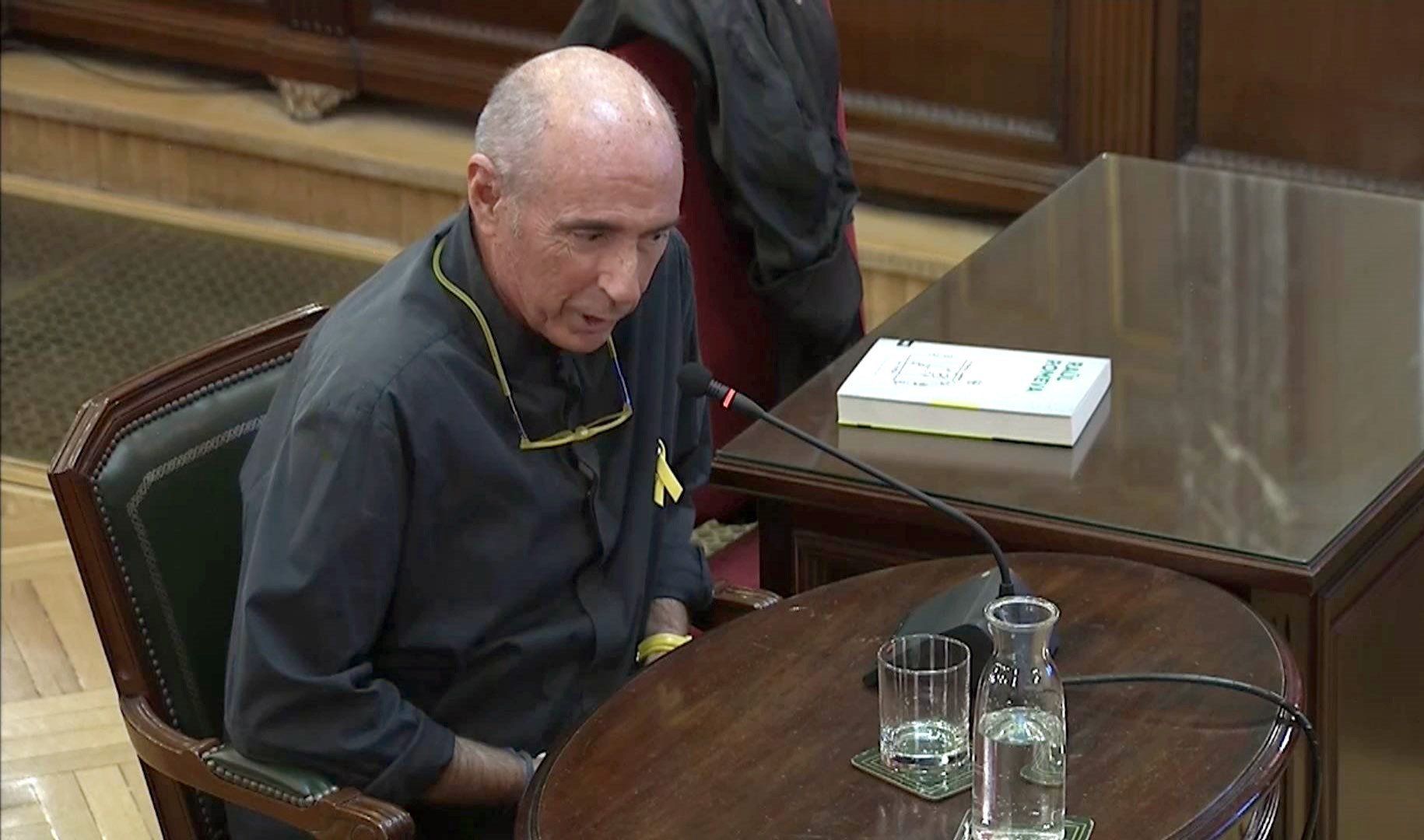

Lluís Llach, who explained that it was he who suggested to Jordi Cuixart and Jordi Sànchez to get on top of the cars in order to address the huge crowd gathered outside the economy ministry that day in Barcelona, had come to court wearing a yellow ribbon which stood out on his dark blue shirt. On the table by his side, he placed a copy of a book by one of the jailed defendants, Raül Romeva's Esperança i Llibertat (Hope and Freedom).

From the moment he took his seat, he insisted on the absence of violence in any Catalan independence protests and in particular during the September 20th protest in Barcelona. He also described in meticulous detail the efforts made by the civil group leaders Sànchez and Cuixart to prevent any kind of incident and facilitate the departure of the judicial team which was searching the Catalan ministry. The two leaders had to cope with heavy booing from the crowd, said the Catalan musician. "Excuse me for saying it, but never on stage have I had a reaction like that," he said, referring to the jeers received by Jordi Cuixart, when he asked the protesters to disperse.

Llach's speech ended a day which was mostly focused on the appearance of international witnesses, which highlighted the deficiencies in the Supreme Court’s translation service, with a Slovenian interpreter unable to translate the legal terms mentioned in questioning and a Portuguese MEP who chose to speak directly in Spanish, while defence lawyer Andreu Van den Eynde lawyer once again had to refine the nuances of the German translator.

International witnesses cause discomfort

The testimonies of the international witnesses were not to the liking of the prosecuting lawyers. Nor was the judge very pleased with Portuguese MEP Ana Gomes when she explained that on 1st October 2017 she was spending the day with her grandchildren when they saw the events that taking place in Catalonia on TV. That same day there were also elections in Portugal, and when she said to her grandchildren they were going to vote, they replied: "but grandma, it’s dangerous, don’t you see what’s happening?". "That’s not here, unfortunately it is in Spain, there’s no danger here," replied the grandmother, in an answer that judge Marchena cut off, arguing that it did not contribute anything to the case.

The declaration, by video conference, of Quebec politician Manon Massé didn’t exactly thrill the prosecutions either. In fact, public prosecutor Consuelo Madrigal asked her if she knew that voting at the Catalan referendum was conducted using a universal census, meaning that any voter could vote at any voting centre "and several times". The protests from the public benches in the court were so loud that the judge called for order and gave the prosecutor a dressing down.

On the other hand, the judge’s commendation for the day went to the court official who has become known to trial viewers only as “Paco”, the audiovisual assistant responsible for the videoconference connection with Canada. After the problems with the translators, the fact that the conference took place without major problems – although beset by interference akin to the sound of a washing machine – was a source of joy for Manuel Marchena. Nobody asked about the message that appeared on the screen for a few moments: "Game time exceeds 80 minutes."