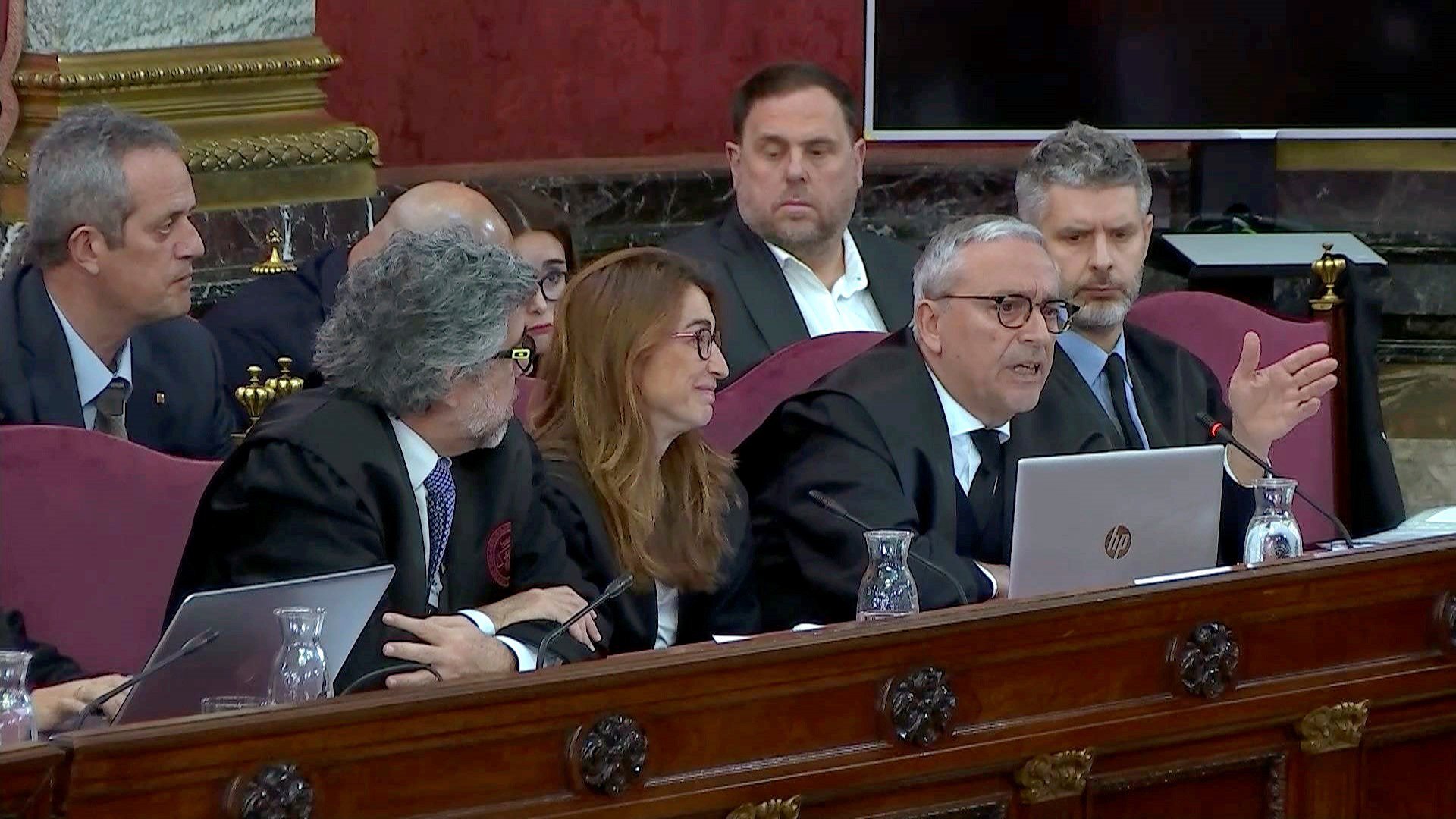

The extraordinary significance of the verdict to be delivered by the court hearing the Catalan independence case was one of the essential aspects underlined as defence lawyers began their closing statements in the four-month trial. Andreu Van den Eynde, lawyer for former Catalan government vice president Oriol Junqueras and foreign minister Raül Romeva, used his final intervention to present this trial as an opportunity to end the Catalonia crisis and "offer an outstretched hand to resolve the conflict." "That's what the verdict should be," he proposed as one of his closing ideas after a two-hour summing up.

Before a packed courtroom, with the trial recapturing its initial level of interest after several weeks of only moderate public attendance, Van den Eynde spoke of the situation in Catalonia, and warned that politics will not disappear and people are not going to stop protesting the current situation of blockage. For this reason, he called on the court to "return the ball to the political arena."

The lawyer explained that in Catalonia what exists is indignation, as evidenced by some of the witnesses heard in the trial, including Basque leader Iñigo Urkullu. It is, he said, neither more nor less than the evolution of the state of disaffection referred to by former Catalan president José Montilla in 2010. "I hope I have helped the court to give the best possible verdicts, but above all, to give verdicts that resolve conflicts, which are the most honest and noble value of the administration of justice," he concluded.

Xavier Melero, lawyer for Catalan interior minister Joaquim Forn, echoed something of the spirit of these words in this morning's second statement. He told the court that this trial must show the people that criminal law "is neither politics nor constitutional law, but rather the application of constitutional law." "Many people have decided that criminal law does not have the instruments or the structures to deal with massive political dissidence. We need to show that from its practical and operational modesty, criminal law is able to give a response to what has been raised here," he urged.

Even as he began, Van Den Eynde had warned that there were no precedents for this trial of political dissidence, which has become a "general case" in which an entire pro-independence political movement is under investigation. He went as far as to say that "an ideology is being persecuted," recalling the details of how the investigation into the leaders of the movement began years ago.

The idea of a coup

Responses to the public prosecutors' characterisation of the independence process as a coup d'état were given in the arguments of both lawyers. In fact, one of those who underwent criticism during the day was legal theorist Hans Kelsen, who had been quoted by prosecutor Javier Zaragoza to accuse the Catalan movement of staging a coup. Van den Eynde regarded the argument as disproven and Melero referred to it as "a well-worn cliché". In fact, Forn's lawyer rebutted Zaragoza for taking advantage of his reference to Kelsen as a way of mentioning Nazism in the court - he had spoken of the persecution suffered by the lawyer - in order to "pollute" the case.

But going beyond that, Melero also warned that the concept of violence must not be banalized. "It is a lack of respect for our dead," he stated, recalling how prosecutor Fidel Cadena had "let it slip out" that in Spanish military history there had been many bloodless uprisings. "The only one he has to mention is July 18th, 1936," he added, in reference to the rebellion by Franco which began Spain's disastrous civil war.

Melero, who asserted that "the only conclusive acts accredited are acts of the abandonment of power" and "that the Catalan government did not declare independence, whatever you say", also rebutted the "postmodern rebellion" label put forward by the public prosecutors, disactivated the narrative of violence and had strong words for the police actions that Civil Guard colonel Diego Pérez de los Cobos had the job of coordinating. The lawyer not only made it clear that the police and their baton charges were not the ones on trial, but he also said that he himself was defending the Civil Guard and the Spanish police, "making clear that it was the ineptitude of how they were led that led them to an impossible situation" which, he said, has caused irreparable damage to their image.

And indeed, before concluding his discourse, Melero gave a round of thank-yous in which, as well as expressing gratitude to the court's audiovisual technician, Paco ("he alone is necessary and the rest of us are contingent") and the court assistant, Piedad, he thanked the police responsible for keeping order and security in the room. "Anyone who criticizes the police doesn't know these police," he warned.

The lawyer finished with a reference to a Spanish movie from 1989, Amanece que no es poco (It's sunrise which is no small thing), a comedy about a Catalan member of the Civil Guard stationed in a town in Albacete province where the worst policing problem is caused by criticizing the US author William Faulkner, because, the story goes, people there are "fanatical" about his work Light in August. "I hope that we can reconstruct a Spain where the only thing we argue about is William Faulkner," he concluded.