The Russian invasion of Ukraine, coupled with the Covid-related economic crisis that had already been raging since 2020, have been the two elements of a perfect storm of inflation which has sent Spanish consumer prices shooting skywards in just the last two months. According to Spanish consumer group Organization of Consumers and Users (OCU), price increases already average 10%.

Regular customers going into their favourite cafés have heard all about it in recent weeks: the apologetic barperson explaining that, sorry, we've had to put prices up. Ten cents more for a café amb llet at a chain that we visit - from €1.35 to €1.45.

But there are also many examples not necessarily linked to the purchase of household commodities. Baby formula milk powder is a staple food whose prices in pharmacies have risen by 20% more on average. In February, we found that Nestlé's Pro NAN cost €22.90, and after the outbreak of the Ukrainian war it ended up climbing to €26.95. A massive rise. You see it in bakeries. The famous Italian recipe bread that you put out on the table at noon to complete the meal now costs €1.35 whereas, five days ago and in the same establishment, it was €1.10.

The small examples that consumers note - even those who weren't in the habit of reviewing the docket when they paid - brings it home how inflation is now close to historical milestones, the last such similar rise being that experienced in 2002 with the change from the peseta to the euro. According to the OCU, average expenditure on food in Spanish and Catalan households rise could rise by about 500 euros over the total of previous years.

The fiercest inflation since the 1970s

The sharpest rises are in olive and sunflower oil, whose prices could even double; but also in margarine, pasta, Canary Islands bananas and salmon, with rises of up to 30%. On average, we now pay almost 10% more on a visit to the supermarket than in 2021. According to the OCU, falling prices are rare - the price of pork filets and onions are curious cases, and to a lesser extent, in some cleaning products. But only 16% of products are now slightly cheaper than before.

All this, in addition to - and partly because of - the higher prices of utilities and fuels, is causing more and more families around the Spanish state to have difficulty coping with their daily expenses. Spain's Consumer Price Index for April is slightly down, from 9.8% a month earlier to 8.4%. It could have hit the ceiling but the uncertainty of it getting worse is a reality.

The World Bank warns that we are facing the greatest commodity crisis in history since that of the 1970s, at the time of the Yom Kippur War in the Middle East. Energy prices are now expected to rise by more than 50% in 2022 before reaching a slight easing by 2023 and 2024. Non-energy prices, including those for agricultural products and metals, will increase by almost 20%.

Comparison of offers

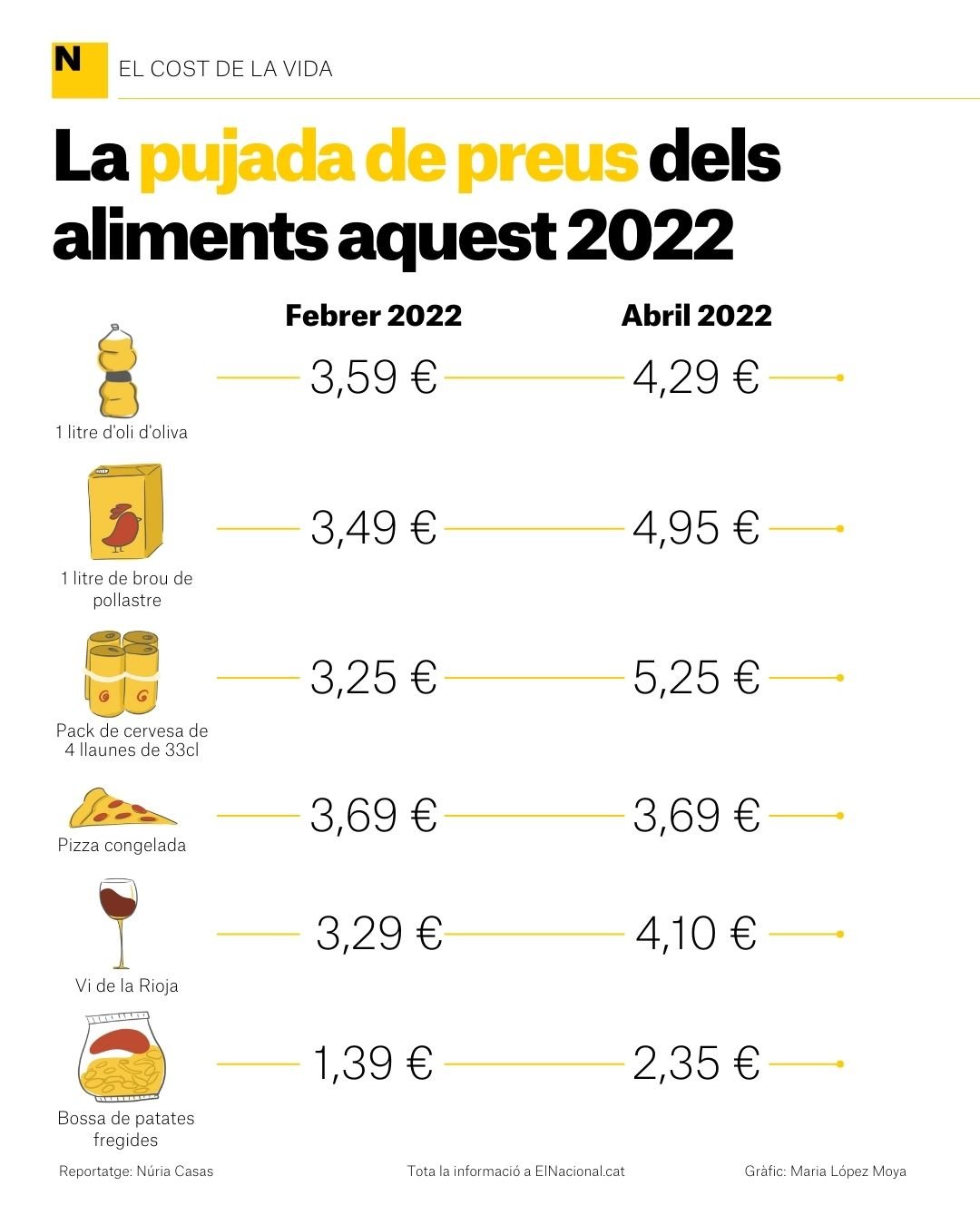

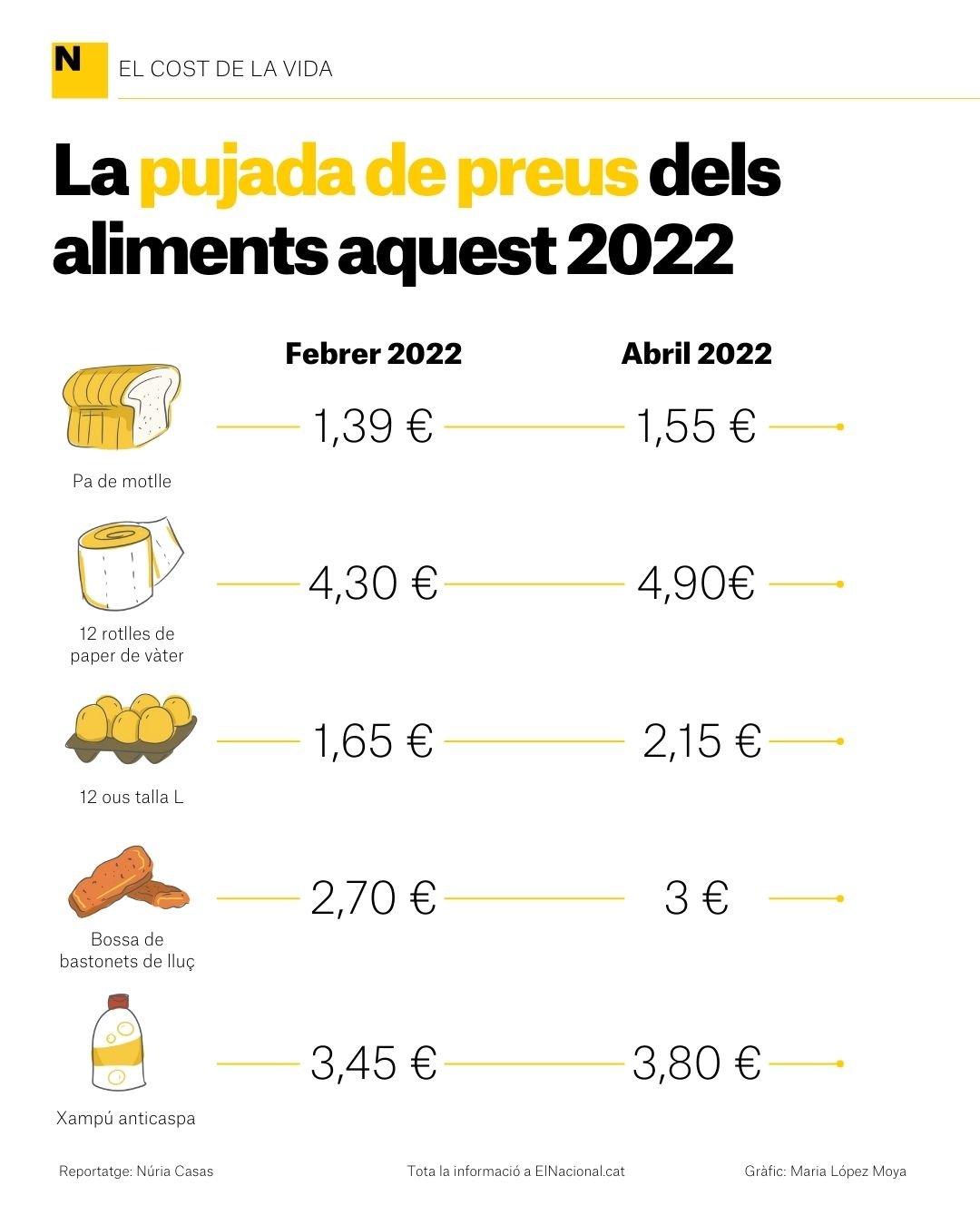

Below, we detail some of the prices that we have compared from a brochure of offers from the same Barcelona supermarket with the same product, giving a clearer idea of the real situation in one neighbourhood. A price comparison with only two months difference in some purchases that are promoted as the offer of the week:

The farmers, on a war footing

But if consumers are uncomfortable, so are producers, distributors, growers and farmers... all those who are part of the chain. One of the sectors which has led to the most complaints is milk. Between December 2021 and March this year, a litre of milk rose in price from 79 to 84 cents at the point of sale, while the base price charged by farmers for producing it has only risen from 31.4 to 32.6 cents, according to Agromuralla.

"In these four months, milk has risen by 6.46% in the supermarket and only by 4.04% for the producer. There is 2% that does not reach us," explains Miguel López, secretary general of the Galicia Consumers' Union. Just as countries are re-thinking their dependence on Russian gas, or reducing connections with third parties in order to cut out rising costs, so too in food do they want to go back, in part, to their origins. "It is essential to move towards food sovereignty. In just three months we have seen the seriousness of having to depend on others and not having the capacity to meet our domestic demand. We know that because of this, some products have inflated up to 200%", concludes López.

And the house brands?

The private or house brands, so often the cheapest in the store, do not escape this rise either. Large supermarkets continue to offer their own cheaper products, but their prices are rising too. One blogger has become very famous for making price comparisons in recent times and posting it in a blog that has been shared by specialized portals. The blog's called 'Joan es mi pastor'. And here are some examples of such products:

These are some big rises for such a short interval. But for the nostalgic, if we expand the perspective over time we might be even more aghast. According to a report by Bankinter, in 2001, the 1 euro coin became treated as "equivalent" to the old 100 pesetas - when officially, what had cost 100 pesetas before should have sold for 60 euro cents. What ensued was a price increase of more than 60% in just a few weeks when the euro became legal tender on January 1st, 2002.

Since then, the various economic crises have generated inflation that has only aggravated the situation. Bankinter confirms what most people have always perceived: that this rise in prices has never been matched by salary rises. While in 2000, the average salary in Spain was 1,493 euros gross per month, it is currently 1,600 euros. That is an increase of 7.16% in the last two decades, far from the increases in the cost of living with the price increases reflected in your shopping basket.