Time stands still. The support of 18 British MPs from four different parties for the Speaker of the Parliament of Catalonia, Carme Forcadell, before the judicial “persecution” she is being subjected to in Spain, has revived the so-called “Catalan case” in the Parliament at Westminster 300 years on.

If the reason is now the criminal charges of Forcadell’s “misfeasance” and “disobedience” to the Constitutional Court for allowing the Catalan chamber to vote on the conclusions of a study by the Commission on the Constituent Process, 300 years ago it was because the Catalans had been abandoned by Her Britannic Majesty in the War of the Spanish Succession, failing in the commitment that their “freedoms” should be respected regardless of the outcome of the conflict. Will that sad story now be repeated when the motion brought by the Scottish National Party MP (SNP) George Kerevan is voted on?

Indeed, on such distant dates —or so near, depending on how you look at it— as are April 3 and 4, 1714, the House of Lords was the scene of an intense debate in which the Whig opposition, which we might consider today as the “progressive” party or faction, charged severely at the Tory government, the “conservative” majority, for having left the Catalans to their fate before Louis XIV and his grandson Philip V. On that occasion, the debate was the result of a parliamentary question made to Queen Anne by 24 Lords.

The shift in British foreign policy had a decisive impact on the Catalan state, leading to its end by (Royal) Right of Conquest, a situation later legitimised by the Nueva Planta decrees that gave rise to the modern Spanish state. Then, as now, the concepts of “rights” and “freedoms” in general, and in relation to Catalonia and Spain in particular, were debated at Westminster.

The Catalans and their rights were sacrificed on the altar of 18th century realpolitik when the British, who decided to embark on the war against the Bourbons on the side of Archduke Charles of Austria with the Treaty of Genoa (1705), considered it time to divide up the European (and American) cake with France. It was the moment of the military and financial collapse of Hapsburg Spain, which had reached its peak and extinction with the heirless death of the sad figure of Charles II, the Bewitched. The about-face in the treatment of the Catalan question by London had come about as of 1710, five years after the concord with the “Vigatans” —the Catalans favourable to the Hapsburgs— as a result of the Tory victory in the elections.

Although Queen Anne defended the commitment with the Catalans to the end, and in the midst of pressure from Catalan diplomats like Pau-Ignasi de Dalmases, whose complaints were at the root of the debate held in Westminster, Tory Secretary of State Bolingbroke gave in to the Bourbons. Utrecht (1713) marked the beginning of the end for the Catalan cause. The enraged Philip V was able to impose his cynical conditions for peace: the Catalans would have, at best, the same rights and privileges as the Castilians who —he said— were “the most beloved subjects” of His Catholic Majesty. Which meant, in practice, the abolition of the Catalans’ system of government and their subjection to the Castilian laws in manifest inequality of conditions, as would soon be evident.

'The Case' and the 'Deplorable History'

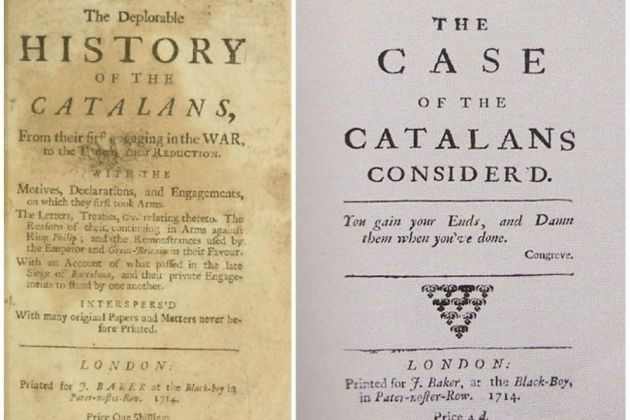

Between March and September 1714, before Barcelona fell to the Bourbon armies, leading to the end of the Catalan state —of the political and legal structures of the Principality of Catalonia— two publications in defence of the Catalans appeared in England cursing the British government’s attitude in the conflict: The Case of Catalans Considered and The Deplorable History of the Catalans. In both publications it was pointed out that by abandoning the Catalans to their fate England was disgracing herself and the cause of freedom in general.

The Case praised and justified the refusal of the Catalans to give in, despite British pressure —Bolingbroke went as far as organising a naval blockade of Barcelona, the former ally— and the superiority of the French and Spanish Bourbon armies: “Their Ancestors were given the privileges they enjoyed for centuries. Are they now to relinquish them without honour and leave behind them a race of slaves? No; They prefer to die all; Either death or freedom, this is their resolute choice.”

Queen Anne of England died on the 1st of August, 1714. She was succeeded to the throne by George I, who like her was a supporter of the cause of the Catalans. But in any case, with its Tory majority, Parliament ruled. In democracy, Parliament always rules, and King George I knew it —as did the Whig government which was formed in 1715, alas too late— and Carme Forcadell knew it on the day that she simply fulfilled the mandate of the Catalan Parliament: to vote.